How I work today looks very different than it did a year ago. Or even a month ago. I’ve always been a generalist. Design was the gateway—making visual things. Making things interactive lead to a technical proficiency and learning how to program. This is now called “design engineering,” but the motivation was to do whatever necessary to see an idea through from conception to completion.

Not thinking along discipline, but intuitively doing what is needed to see a project through, is the direct result of my schooling experience.

I stopped attending school at age ten. Fifth grade was the last of it. We tried homeschooling, and I briefly had a curriculum, but I was online, and it quickly became purely interest driven. Loosely inspired by Montessori, but effectively unschooling. Not learning as defined by topic, but by curiosity and interest.

Because of this, I feel like I’ve been doing the same thing along a continuous meandering path since that time. It was only possible by having direct access to the open internet, and the ability for anyone to self publish permissionlessly. This enabled following my nose through everything and anything.

I’ve felt a similar increased ability to run while using nascent tools for programming assisted by AI recently.

Being a generalist and generating connections across wide ranges has guided me to leading product at startups I’ve either co-founded or joined as senior leadership. It involves many parallel feedback loops of direction and review. “Prompting” in a sense. There is a lot of gluing things together into a cohesive whole. Doing it effectively requires a deep understanding of everything a product requires—ideation, research, design, engineering, positioning, operations, etc…

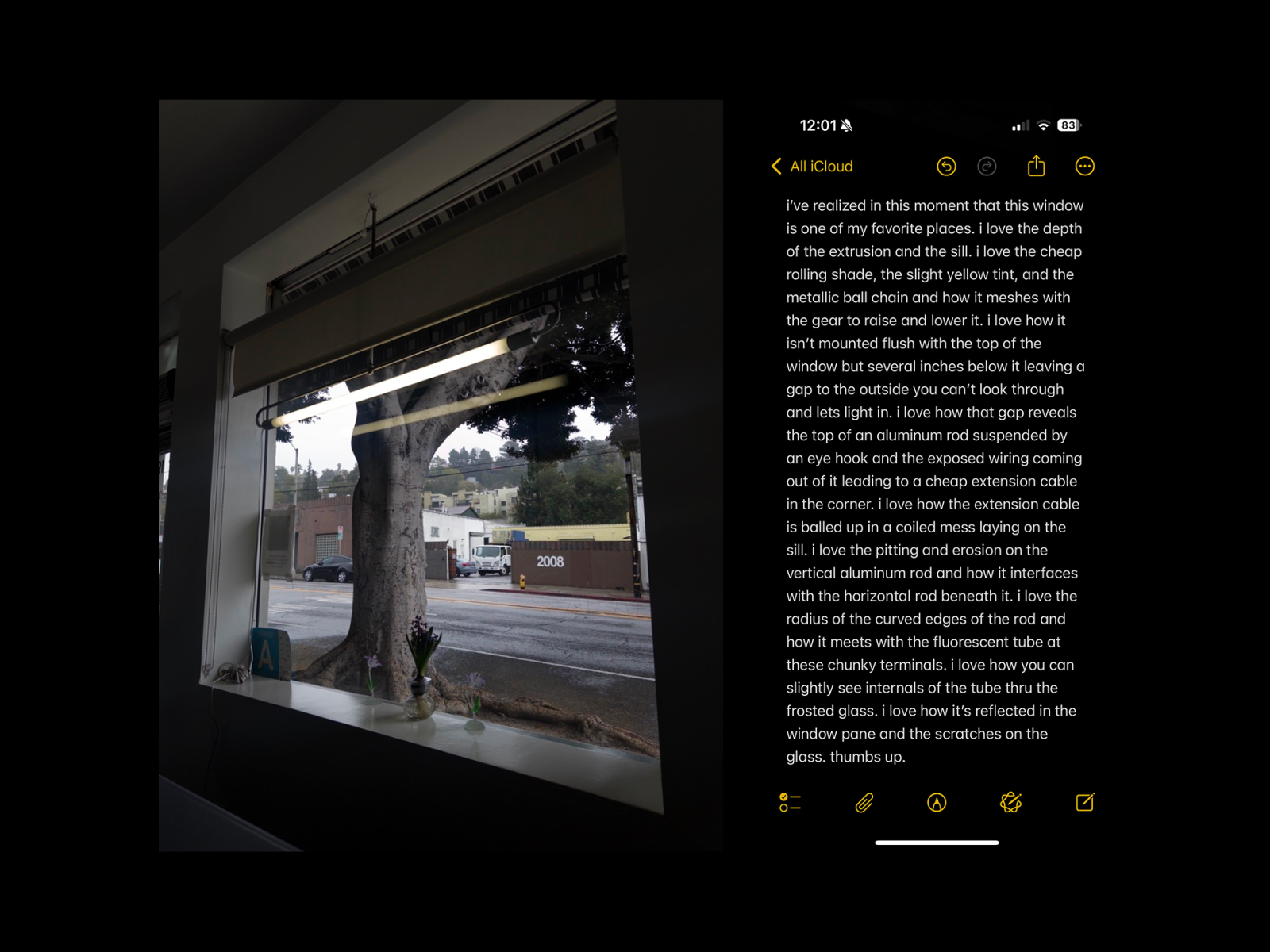

I’m typically involved in the early and final stages of everything. Conception, polish, and giving the thumbs up. Call it the first and final 15%.

Finding myself in this position is a reflection of being a generalist with a slight “T” shape for design. Everything is driven by the idea, and I do whatever is necessary to enable the idea’s existence.

I love working with a team. A strong collaborative partnership that clicks is a gift. AI is not going to replace that.

But there is a kind of magic when you’re in the zone. Trying to keep up with an idea and holding on for the ride. AI tooling has recently gained the ability to do that middle 70% of execution remarkably well. Of course you have to lay the groundwork and follow it up with polish. But it’s exceptionally good at high velocity work with someone leading the product with care.

Working in this way has become known as “vibe coding.” A term that checks out. It’s very intuition based. Kind of like sailing. You’re at the helm, and you set the direction, but how the AI responds influences the path you take, just like the sea. It reveals things along the way you may not have stumbled into otherwise.

Currently I’m using Cursor, Claude Code, and Devin to work on Cycle. I’m not a great backend engineer, so I’m using it to write database migrations and API endpoints. I can pull down generated types from Supabase and reference the schema when using Claude Code to make a pull request with entirely new surfaces. Yes, it often takes a few hours of finesse to get it where I’d want it to be, but compare that to a week or two working with a team and the latency of revisions.

To my unschooled brain the ability to observe the AI is my greatest excitement. When working with a team you often must delegate. Many find this difficult. There aren’t enough hours in the day for you to do it all, and it’d drive anyone mad being on the receiving end of someone hovering the entire process in order to sponge it up, or asking for a detailed explanation of each decision to satisfy curiosity.

When prompting AI you see the process dictated in real time and are able to follow along. You see the logic playing out. You can ask for detailed explanations after a result has been generated. You can zero in on specific areas of personal confusion. It helps you better understand and think about the product you’re creating.

There is a misconception that the primary affordance of AI is increasing velocity. Of speeding up arriving at an output. In a sense this is true, in the same way a pencil speeds up your ability to make a legible mark on paper. But it is also a remarkable learning tool. You can ask limitless numbers of questions to satisfy your curiosity without, well, driving it nuts.

None of this is without contention. I have no idea the implications of what this means for labor, creative or otherwise. I don’t believe being a cog in the machine is sustainable. That detached phone it in mentality. The places where it’s possible will not exist much longer. Maybe that is ok. I don’t think it’s good to feel detachment from what you’re doing. It’s good to care. It may be difficult, and you may experience disappointment and pain by doing that, but it’s real. It’s important to be hopeful, and that involves risk, as does anything good.

For now, I’m continuing to follow my nose.